Author Zadie Smith once remarked, “Genre cannot contain Ursula Le Guin: she is a genre in herself.” One of the most celebrated writers in all of science fiction, and one of the greatest American novelists, Ursula Le Guin’s legacy perseveres in all fantasy: from Star Trek to Studio Ghibli, she’s beloved by readers and writers alike. But Ursula K. Le Guin doesn’t write about aliens and wizards and time travel, although her extensive oeuvre includes all of these things. What Le Guin really writes about about is storytelling, equilibrium, and the material power of words.

In Tales from Earthsea, a wizard controls weather and soothes dragons by invoking their names; in Always Coming Home, Le Guin breathes life into an entire civilization with poetry and short stories; and in “The Shobies’ Story,” storytelling is the engine for faster-than-light travel. In one of her earliest novels, City of Illusions, she writes about the Way. In fact, Le Guin was a lifelong student of Taoism, often exploring themes of balance, spontaneity, and wholeness. Her imagination, coupled with her poetic exploration of philosophy, endears her to readers of all types – whether fans of science fiction or not.

In response to the accusation that science fiction is just “escapism,” Le Guin herself says it best: “The direction of escape is toward freedom.”

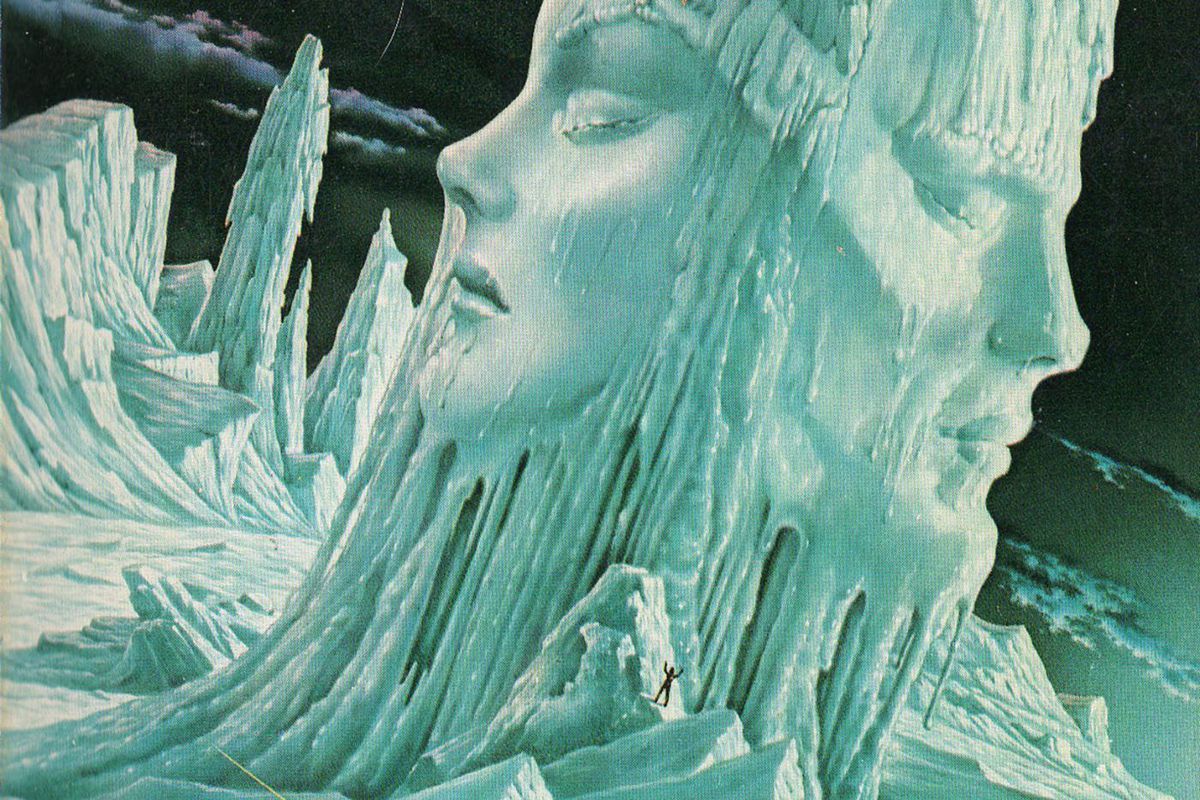

The Left Hand of Darkness

When people ask me where to start with Ursula Le Guin’s novels, my response is always the same: The Left Hand of Darkness. This 1969 novel is one of the most celebrated epics in all of sci-fi, exploring themes such as space exploration and future history in one of the most ambitious projects of world-building ever written.

But what makes The Left Hand of Darkness visionary is its destruction of the gender binary. Gethen, also known as Winter, is a planet home to people who shift between mother and father, woman and man. Fundamentally, this is a book about balance between light and darkness – as its title suggests – and also between mythology and truth.

The Earthsea series

Le Guin’s high fantasy Earthsea series, which contains five stories published between 1968 and 2001, are my personal favorite Le Guin stories. Although these aren’t science fiction, I’m including this series as a must-read for any Le Guin fan. Between Earthsea and Left Hand of Darkness, it’d be difficult to say which is more beloved or famous – and I think Earthsea would be an equally good place to start for those new to her work.

Mysterious and reflective, these books incorporate themes frequently explored by the author, most notably Taoism and the power of words to shape reality, often called “true name” theory. In the 1980s, Hayao Miyazaki – whose work also explores these themes, like equilibrium in Nausicaä and “true names” in Spirited Away – approached Le Guin about adapting Earthsea into a film. This project was eventually taken over by his son, Goro Miyazaki.

Short stories

Perhaps Le Guin’s most famous short story, “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” (1973) is often used in high school classrooms to illustrate utopianism. Omelas is a prosperous city of music, culture, and celebrations; but when children of Omelas come of age, they must confront the dark secret on which their perfect society rests. Only a few pages long, this story is deceptively simple – often explained as allegory to a simple question: can the abject suffering of some justify the happiness of many? But below the surface, it also reveals the author’s own “political unconscious,” ideas which she draws from socialism, Dostoyevsky, and William James.

For a concise introduction to Le Guin’s science fiction, The Shobies’ Story (1990) is a great novella to start with. The story follows a voluntary group of test subjects on a faster-than-light journey powered by a mysterious technology. The prose are distinct from her earlier works, but many of her themes are nonetheless the same.

The Dispossessed

A lot of sci-fi from the 50s to the 70s is dated in its social themes, whether it be treatment of gender, politics, or American Exceptionalism. But Le Guin’s books always feel relevant and brave – even decades after their publication. Winner of the Hugo, Nebula, and Locus awards, there’s no doubt that The Dispossessed (1974) defied the mores of its time.

Exploring themes such as Taoism, capitalism, anarchism, Marxism, and utopianism (the original title was The Dispossessed: An Ambiguous Utopia), this book is definitive of Le Guin’s style. It takes place in the universe of the Hainish Cycle, Le Guin’s galactic federation in which many of her stories are set. It’s a philosophical exploration of two worlds: a wealthy planet of elites, its satellite on which private property does not exist, and a physicist whose dream is to bridge these two planets with a device that enables faster-than-light communication.

City of Illusions

An earlier Le Guin novel, City of Illusions (1967) is a worthy introduction to her Hainish Cycle – the universe in which many of her stories are set. The opening of this book, quoted below, draws from the Tao Te Ching, perhaps the single-most influence on her writing, and of which she was a student for decades.

“Imagine darkness.

City of Illusions (1967) by Ursula K. Le Guin

In the darkness that faces outward from the sun a mute spirit woke. Wholly involved in chaos, he knew no pattern. He had no language, and did not know the darkness to be night.

As unremembered light brightened around him he moved… he had no way through the world in which he was, for a way implies a beginning and an end.”

Lao Tzu : Tao Te Ching : A Book About the Way and the Power of the Way, with notes from Ursula K. Le Guin

If you’ve made it this far down this post, you’ll have noticed that the Tao undergirds all of Le Guin’s writing. A student of the Tao Te Ching for over 40 years, Le Guin appreciated all aspects of this book: from its humor, to its enigmatic poetry, to its forever-relevant philosophy. This newer translation is by no means the best, though it’s meant to be more relatable to a modern reader. But for Le Guin’s footnotes that accompany many of the chapters, it’s worth keeping by your bedside for uplifting and contemplative ideas to meditate on.